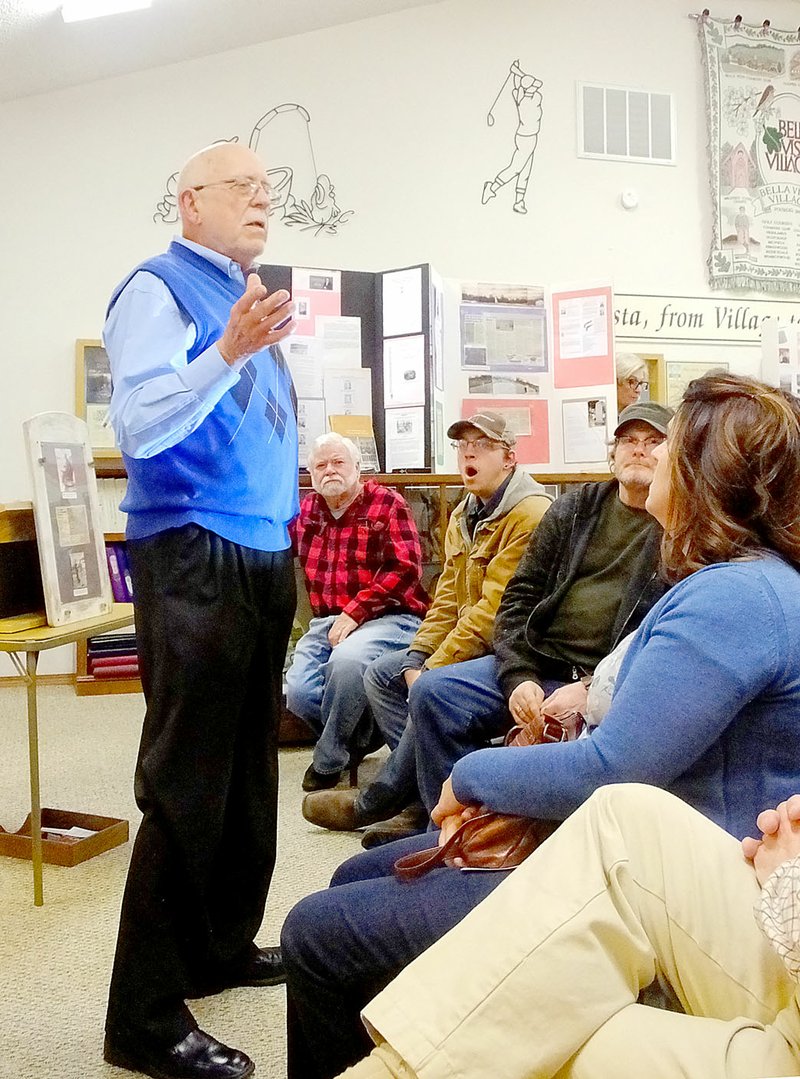

A meeting of the Butterfield Trail Questers was opened up to not only other Questers, but also to the public and it drew a crowd that filled the back room of the Bella Vista History Museum. The guest speaker told them a story about murder, theft and a cover-up that all started in Northwest Arkansas.

The Questers are a group interested in history. Their meetings seldom draw a large crowd.

The speaker for this one was retired college administrator Frank Terry who is a direct descendant of one of the few survivors of the Mountain Meadow Massacre.

It began, Taylor said, when several families around Harrison, Ark., decided to move to California. They met up outside of Harrison in the spring of 1857 and formed a well-provisioned wagon train with 22 wagons, 186 oxen and 798 head of cattle. The train traveled about 16 miles a day. It was a long trip.

Meanwhile, the Mormon Church, under the leadership of Brigham Young was involved in a dispute with the federal government which is sometimes called the Utah War. The group had been pushed out of several states, including Missouri before settling in Utah in 1847. Young ruled his followers as governor, but it was more of a theocracy than a democracy.

Young had 20 wives and 47 children, Terry told the audience gathered at the museum.

Like other wagon trains, the group from Arkansas stopped in Salt Lake City to buy needed supplies, but no one would sell to them. Eventually, they heard about a place where they could camp and rest for a few days, so they proceeded to Mountain Meadow.

The attack took place over several days, Terry said. The travelers were able to defend themselves for a few days, but the scouts they sent for help were killed. Eventually, on Sept. 11, 1857, some riders approached under a white flag. By then the wagon train was low on water and ammunition, so they agreed to the terms that were offered.

They allowed the women and children to be separated, and each man was given an escort as they moved away from the wagons. But then, an order was given and every one of the escorts turned and shot the man he was escorting. The women panicked and tried to get away, but they were also executed along with all the children older than the age of 7. One hundred and twenty people were killed. The only survivors were the 17 children who were 6 years old or younger.

The wagons and the animals were all brought to the tithing office, Terry said, and became the property of the church.

A year later, after other wagon trains reported seeing bodies in the area, federal officers arrived to investigate and the locals tried to lay the blame on Indians. A few Indians may have been present, Terry conceded, but it was the white settlers who were guilty.

A few years later one man was tried and eventually executed for the crime, but he was just a scapegoat, Terry said.

The federal officers found the 17 children and brought them back to Arkansas where they were raised by relatives.

Terry didn't have a definitive answer as to why the massacre happened. The Mormons who carried it out might have been afraid of the federal government, or maybe it was revenge for the persecution they had endured in Missouri. There would have been an element of greed since the community took all the goods for themselves.

"It's a story of good people being in the wrong place at the wrong time," he said.

There's been a lot written about the incident, he said. He had several handouts with him for the audience, including a 1938 interview with his great, great grandmother Betty Baker Terry.

Two men listening in the audience had a few questions. Johnny Hudson and his brother, Billy Joe Hudson, are also descendants of Betty Baker Terry. Although the men didn't know each other, they agreed they must be cousins.

Johnny Hudson said he saw the museum event on Facebook and called his brother immediately so they could attend. His family has a handwritten document about the massacre that was passed down, but he isn't sure who has it now.

It was Susan Olsen who set up the event for her group of Questers. She heard about the massacre and mentioned it in passing when she was playing Bunco. It turned out she was playing with Frank Terry's wife. Originally from Harrison, Frank Terry now lives in Bella Vista. He has spent hours researching the subject and visited the site on more than one occasion.

General News on 03/07/2018