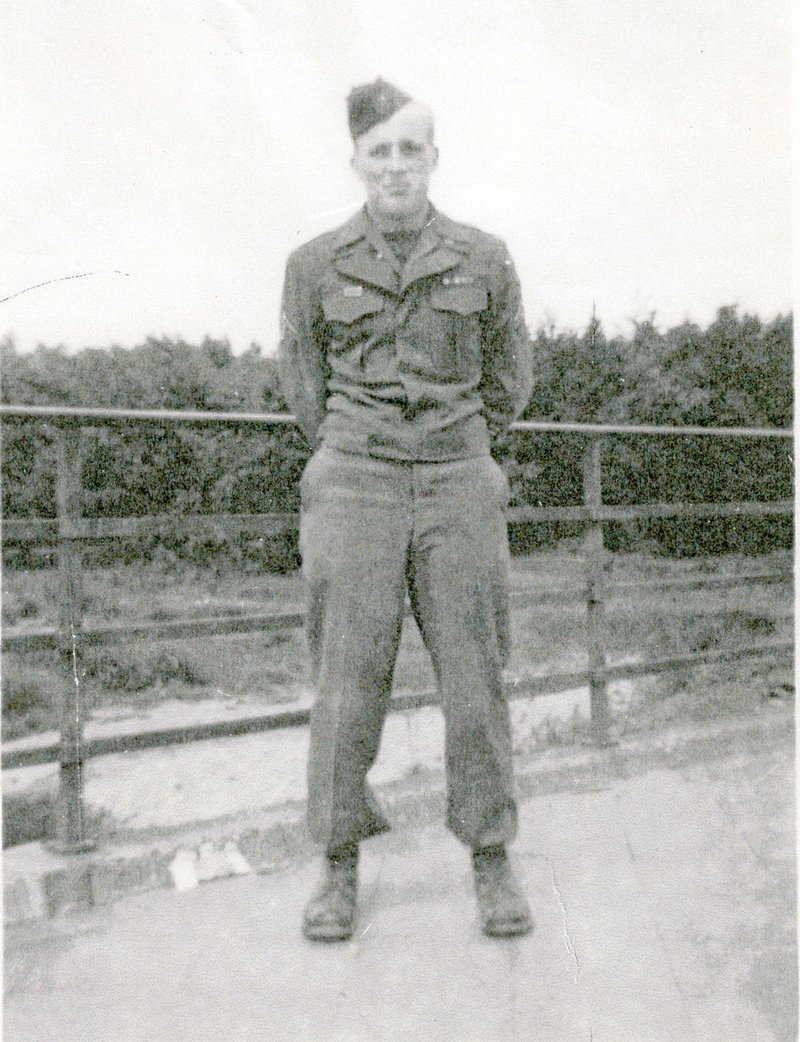

Andy Anderson, a resident of Brookfield Assisted Living Center, fought in Europe during the Second World War in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers from 1943 to 1945, where he achieved the rank of staff sergeant.

As an engineer, he said, he did a little bit of everything -- they built bridges and roads, for instance.

More veterans’ stories are one Page 1B of this issue of The Weekly Vista.

Anderson was part of the first group of soldiers to invade Europe, he said, and he also fought in the Battle of the Bulge. Moreover, he was among the U.S. soldiers who met the Russians at the Elbe River.

He was 20 years old when he was put on a boat to invade Europe, he said, and one of his main jobs was setting up a defensive perimeter, complete with water-cooled .30 caliber machine guns, on Omaha Beach.

"I was carrying my M1, my gas mask, my water, my backpack," he said. And on top of that, he had to haul the machine gun and enough gear to set it up.

It wasn't easy, he said, to set anything up in the beach's sand and loose rock. The deeper he tried to dig, the more the hole would fill in.

According to a letter he wrote to Bonnie Buchanan -- before she became Bonnie Anderson -- he may have been one of the first to land with heavy equipment, and it may be a small miracle they landed at all, because the German soldiers were focusing their fire on heavy-equipment-carrying boats.

It was a protracted struggle, he wrote. The soldiers that made it in ahead of him were expected to stop the German small-arms fire in roughly an hour, but six hours into it there was still plenty of fire.

The small-arms fire, he wrote, was problematic, but shelling was also constant.

"All through that day we were shelled," he wrote. "God, it's hell when you hear that fluttering sound they make. When you hear the fluttering you know it's going to land close."

They later found documentation, he wrote, with the entire beach mapped out in detail, including the exact range of nearly every spot on the beach from any given gun emplacement. This, he wrote, explained the Germans' accuracy.

After that, he made it to the infamous Battle of the Bulge.

"Colder than hell," he immediately recalled. "At one point, we lost more guys to the frostbite than we lost to the Germans."

Between the cold, the amount of time a soldier spent motionless in a foxhole and the possibility of getting wet from snow, frostbite could be hard to avoid.

The most memorable event for him during the battle, he said, had nothing to do with the fighting -- it was just an accident courtesy of the ice and snow. He was on a night patrol with his squad, all in the back of a truck. They reached Spa, Belgium, and had to turn back, he said.

On the return, they came to a steep hill. With the ice and snow, the truck's tires just couldn't get a good hold, he said, and they found themselves unable to get more than about halfway up.

And then they saw headlights at the top of the hill.

Traveling in the opposite direction, he said, was another vehicle hauling a tank that had broken down. As soon as its driver saw the truck with Anderson and his squad, he got on the brakes, but the hauler couldn't stop.

The trailer and the tank pirouetted down the hill and Anderson jumped onto the ice to avoid it.

Once everything stopped and everyone caught their breath, he said, they discovered the tank's tread had been thrown off the trailer.

"How they got past us, I still don't know," he said. "I shouldn't be alive."

Meeting Russians at the Elbe, he said, was a far more lighthearted affair.

"They had Russian soldiers on one end of the bridge and Americans on the other," he said. "But they came across and I got a drink of Vodka, I remember that."

After the war, he said, he came back home to Centerville, Iowa. There wasn't a lot of difficulty transitioning back to normal, everyday life, he said. But he did need a job. He hopped on a train to Denver, he said, and learned to be a watchmaker.

At the height of his career, he said, he had three jewelry stores, though now he's downsized to one.

The Andersons said they moved to Bella Vista a little over a decade ago, and they've enjoyed their time here.

Their apartment at Brookfield still has thorough documentation of his service. There's a display case full of officer coins he's collected over the years, a plaque with his name on it, and another with his unit.

There are a handful of books full of wartime photographs and writing from soldiers. There's a compiled history of his unit, the 348th Combat Engineers.

Two years ago, he said, he was able to return to Omaha Beach. The College of the Ozarks has a program, he said, to let veterans revisit battlegrounds they fought on years ago.

He was part of a group that got to revisit Omaha Beach.

The beach, he said, was home to a victory monument that had been defaced over the years -- someone had taken the plaque from it. His group, he said, helped to restore and rededicate a victory monument during the battle's 70th anniversary.

Halfway across the world, home in Bella Vista, he keeps a series of stones commemorating that anniversary and a vial of Omaha Beach sand on display in his living room.

General News on 11/09/2016